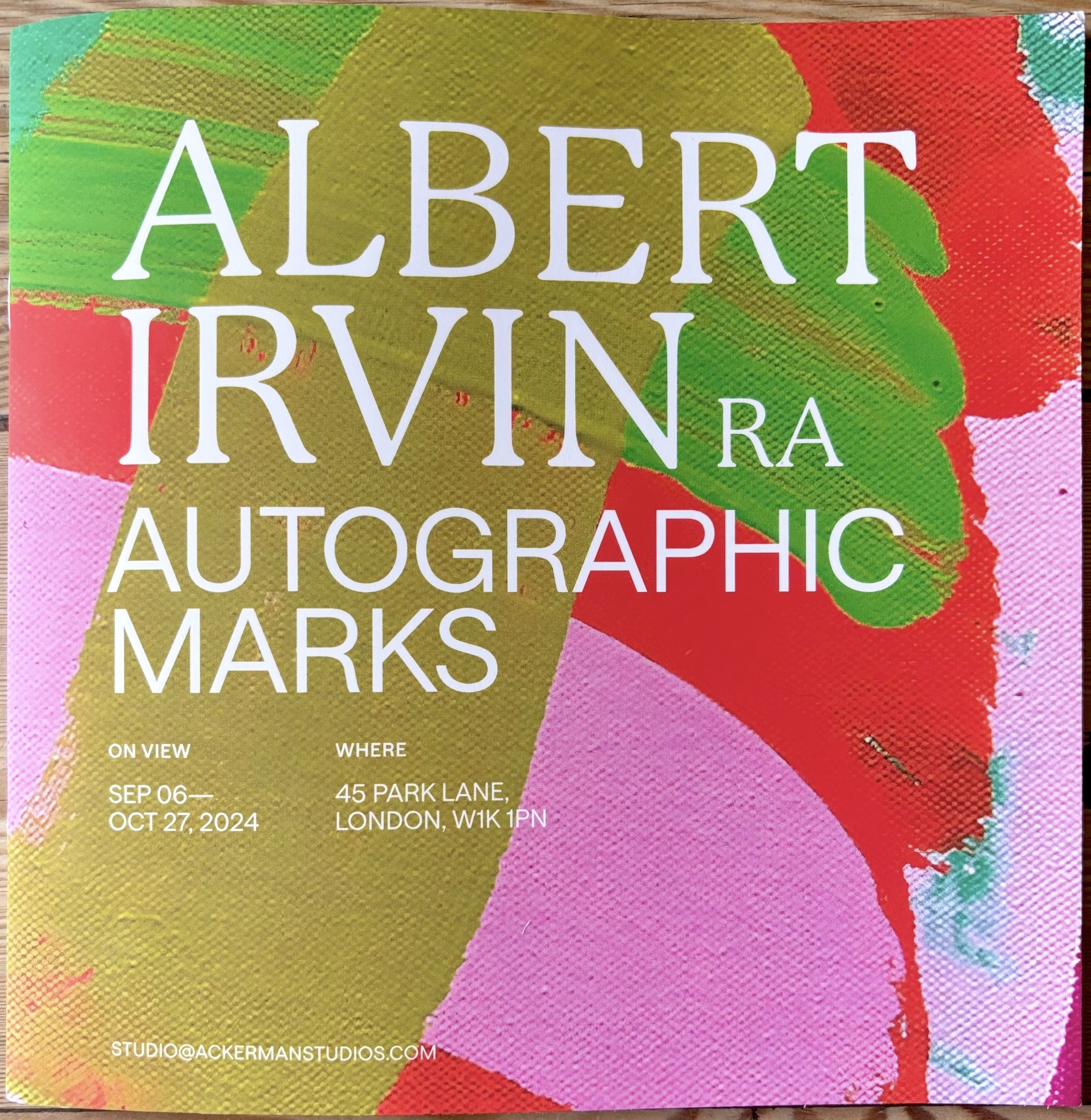

ALBERT IRVIN RA | AUTOGRAPHIC MARKS

INTENSION AND DESIRE

The last time I went to Bert Irvin’s studio was in 1996 to talk about an essay I was to write about ELY, 1995, a huge painting that was to be shown at Gimpel Fils. It was good, just now, but sad, to be reminded, of the structures, systems, material and processes used to achieve such authority in the work. To be reminded, so many years after Bert’s death, so many years anyway, of his full commitment to result, his desire for an apparent photo finish between intention and desire. A painting is a performance, each time, when it arrives, but the making of a painting, and also a print in Bert’s case, is really about practice, trial, error, notion, questioning, and even discussion. The studio is still full of the painted strips of colour he used to hold up in front of an ongoing work, to see a way forward without fixing forever with paint. He would also use Polaroids to map change, as it were, but all this was backstage, to ultimately get it right. The idea that all can be achieved with an instant fit of truth to material and gesture is somewhat naive. Instead of bringing order out of chaos, Irvin orchestrated with real intention a build-up of colour, stroke, and appropriate scale.

There is so much in being fresh and clear; from the translucent paintings like Celebration, 1972, almost water colour in working, through to later more solid opaque paintings, the canvas for Bert, was a huge, ground, or place, that could be inhabited cherished and watched over. The work is titled after places, always, but just once Nicolson,1989, his wife Betty’s, maiden name. It is always authoritative and sensible to give a child, exhibition, television series or novel a place name, and Irvin’s titles allow the chance to sense a level of gravity and motion, to admit that there is a shared point of democracy to begin with. We are from this planet, after all, not outer space. As Bert told Judith Bompas when she wrote in the RA Magazine an article in praise of him at 80, ‘My paintings are abstract, but they are informed by my being in the world, and by my journey through the world’. ‘For me the experience is urban, traversing streets, on foot or on buses, travelling underground in tube trains, seeing through windows or door frames into spaces beyond, past intervening figures.’ Bompas’s language, in turn, reflects a sense of joy and respect, with words such as ‘vibrant’ ‘exuberant’ and ‘crescendo’ describing the work.1

Two words, Painterly and Constructivism, written on the wall of Irvin’s studio, reflecting a simple polarisation in discussions about painting, that are yet successfully brought together and resolved in the work. Irvin constructed a state of mind, by hook or crook, with trial and little permanent error. The work, neither expressive in the simplistic sense of a relation between mark making and result, contains both. The false distinction between conceptual and expressive art is one to which Irvin, educated and educator, would never subscribe. His work was not from observation but was about activity and transportation. He, wanted to see first, and the paintings, and prints, are about a one-to-one sense of discovery across the surface. His work, the end, the conclusion, is not purely a sum of the parts that make it up, it is also about decisions to leave gestures behind, and colours out.

As stated, Bert just loved being on transport, making his way across and around the city. The paintings, which are a sum of his existence and this movement through, come from a humanistic relation to place and the figure. It was suggested that Irvin came to abstraction through De Kooning who always carried a level, or vestige, of figuration in the shapes that can be read as a body in his painting. Basil Beattie, his studio neighbour, friend and celebrated painter, suggested, that De Kooning, who Bert saw an exhibition of at the Tate in 1956, showed Bert a ‘way in’ in the transition from earlier more apparently kitchen sink painting through to the apparently abstract.2 Having been conscripted to the RAF during WWII, Irvin had an independence and mature approach to making art. With something of the swagger and confidence perhaps picked up from American Airman, Bert who like many artists had served in the war, and had gone to art school later than usual, ‘was less inclined to be told what to do’ Tim Hilton wrote in 1980.3

Irvin, who started with the build-up of translucent paint, and fascinatedly swore earlier on that he would not use, white, like a watercolourist believing that the light remains in the reflection back from the surface. Irvin’s watercolours are different altogether in fact. Constructions where translucency builds to make wads and solidities of colour, their range of solidity and diffusion make something particular in his respect for the honestly of the process, the result here somehow taken out of the artist’s hands. Irvin understood how to make something work, and organised his body, time, and psyche to achieve that. He was strategic in his joy and generosity and wrote brilliantly, and clearly. As a tutor and an artist, his thorough and straight forward approach, encouraged strength in others. The nature of the work is that strange, and solid, perhaps unromantic, though romantic, combination of effect and a lack of personal angst. Things may have gone back the other way, with art more rather than less personalised, Irvin, on the other hand in his notes, teaching and lectures, was honest about his respectful relation to art and other artists, to his own expectation.

The studio is divided into two spaces, one for storage and reference, with bookshelves still ordered with monographs of Velázquez, Vermeer and Vuillard, next to each other and books on Baselitz and Beattie on the shelf below. The other part, however, is a centre for action. The division a metaphor for Irvin’s mind, perhaps. The sense of unfettered joy, when painting, for instance, is about feeling free and able to move about, to being able to think in physical form. To feel unencumbered in a state of making, to feel both safe and free, in accessing the disturbing and often contradictory combinations of body, mind, chance and knowledge; to be able to embrace risk as well as reason. Irvin often worked to huge scale, on huge canvases on the floor. This desire for scale coming from a first impression of Abstract Expressionism from the USA. The lack of control, the relation between the artist and the surface, an expanse that, as Beattie says probably came from the Federal Arts Project, ‘it’s a form of mural painting’ Irvin’s paintings deal with control. The line gets thicker, the brush stroke larger in a scaling up, there is no frenetic build up, somehow, towards the very end, and Irvin was seen to evolve and flower further when he was older. The scale is essential, the sometime enormity, means that for the artist there is no total visual control, the painting is not purely an image. Long sticks, three pronged brushes, Irvin could never do a painting by accident. This is the principle, and the highly respectable, respectful, content of the paintings. The print making process was very important to Irvin and suited him strongly because of the stages naturally held within it. Such anti-expressive expression is a staged process of blanking out, gesture and drifts, used like punctuation over and over, brought together, in stages, with the help of a printmaker friend talking about what might, and should not, happen.

Judith Bompas in RA Magazine in 2002 in celebration of Bert’s 80th birthday.

“Several Other Gears” An Interview with Basil Beattie in Albert Irvin and Abstract Expressionism RWA Catalogue, 2018.

Tim Hilton essay in Albert Irvin Painting 1979/80 Acme Gallery catalogue, 1980.

Copyright Sacha Craddock July 2024